Sir Thomas More - Historical Profile

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

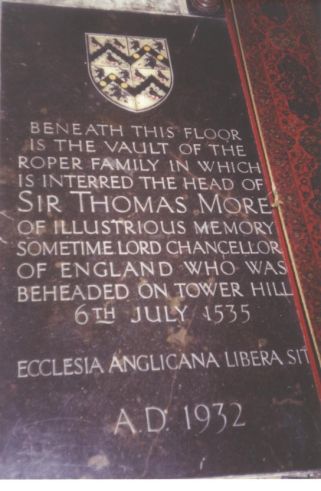

| The History of 1478 - 1535 (aged 57) "No famous family, but of honest stock" Epitaph on More's tomb, chosen by himself. Click EasyEdit to update this page! (Don't see the EasyEdit button above? <a href="/#signin" target="_self">Sign in</a> or <a href="/accountnew" target="_self">Sign up</a>.) |

INTERESTING FACTS:

"Shortly after Christmas 1533, Thomas Cromwell received an anonymous tip-off that Thomas More was preparing to publish an attack on Henry. Unable to take the risk, Cromwell raided the shop of More's publisher. Nothing was found, and More told Cromwell in a letter that he hadn't written anything recently, apart from a book defending the theology of the mass.... A month before Anne Boleyn's coronation in 1533, More had published 'The Apology of Sir Thomas More', a long book defending the old order in the Catholic Church. More advised 'every good Christian man and woman' to 'stand by the old, without the contrary change of any point of our old belief for anything brought up for new'. He urged all Henry's subjects 'to stand to the common well-known belief of the common-known Catholic Church of all Christian people, such faith as by yourself, and your fathers, and your grandfathers, you have known to be believed, and have (over that) heard by them that the contrary was in the times of their fathers and their grandfathers also taken evermore for heresy'. ... When Thomas More was a prisoner in the Tower, he and Bishop John Fisher persuaded one of the lieutenant of the Tower's servants, George Gold, to carry letters between them. Asking what he should do if he were caught and questioned, Gold was told by both More and Fisher to deny everything as by English law he was not bound to incriminate himself. But 'if he were sworn upon a book [i.e. questioned on oath], that then ... he should discharge his conscience and say the truth.' Thomas More thought that dissimulation and deceit were morally justifiable in the face of Henry's cruelty, except on oath." [Source: Historian John Guy on tudors.org]

| Hans Holbein's sketch of Thomas More

This letter would later be edited by Catholic writers to exclude the part where More describes Anne as 'noble.' More also wrote on the subject of the Boleyn marriage that "[I] neither murmur at it nor dispute upon it, nor never did nor will... I faithfully pray to God for his Grace and hers both long to live and well, and their noble issue too..." <a class="external" href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Ives" rel="nofollow" target="_blank" title="Eric Ives">Eric W. Ives</a>, The Life and Death of <a class="external" href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Boleyn" rel="nofollow" target="_blank" title="Anne Boleyn">Anne Boleyn</a> (2004), p. 47. Revisionist history was rampantly practiced by both Catholics and Reformers after the deaths of Sir Thomas More and Anne Boleyn. However, More did not attend Anne's coronation on June 1st, 1533. It was reported in Europe that the real reason for More's condemnation was his refusal to assent to the 'Boleyn Marriage,' although this was never put into words by More himself.

| |||

| <a class="external" href="http://www.thomasmorestudies.org/g22.html#" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">  </a> </a> Margaret's Final Farewell to More Painting at Tyburn Convent, London | ||||

Click LINKS for more information:

|

| |||

| Thomas More's Last Letter "Our Lord bless you, good daughter, and your good husband, and your little boy, and all yours, and all my children, and all my god-children and all our friends. Recommend me when ye may to my good daughter Cecily, whom I beseech Our Lord to comfort; and I send her my blessing and to all her children, and pray her to pray for me. I send her a handkercher, and God comfort my good son, her husband. My good daughter Daunce hath the picture in parchment that you delivered me from my Lady Coniers, her name on the back. Show her that I heartily pray her that you may send it in my name to her again, for a token from me to pray for me. I like special well Dorothy Colly. I pray you be good unto her. I would wot whether this be she that you wrote me of. If not, yet I pray you be good to the other as you may in her affliction, and to my good daughter Jane Aleyn too. Give her, I pray you, some kind answer, for she sued hitherto me this day to pray you be good to her. I cumber you, good Margaret, much, but I would be sorry if it should be any longer than to-morrow, for it is St. Thomas's even, and the utas of St. Peter; and therefore, to-morrow long I to go to God. It were a day very meet and convenient for me. I never liked your manner towards me better than when you kissed me last; for I love when daughterly love and dear charity hath no leisure to look to worldly courtesy. Farewell, my dear child, and pray for me, and I shall for you and all your friends, that we may merrily meet in heaven. I thank you for your great cost. I send now my good daughter Clement her algorism stone, and I send her and my godson and all hers God's blessing and mine. I pray you at time convenient recommend me to my good son John More. I liked well his natural fashion. Our Lord bless him and his good wife, my loving daughter, to whom I pray him to be good, as he hath great cause; and that, if the land of mine come to his hands, he break not my will concerning his sister Daunce. And the Lord bless Thomas and Austin, and all that they shall have." | More bidding his daughter Margaret Roper farewell

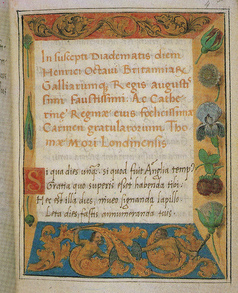

Thomas More’s body of Latin verse includes five poems, which were written in celebration of the coronation of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon on June 24, 1509. This copy was probably the one presented to the royal couple. It is written in an elegant italic script, and is decorated in the Flemish style. | |||

| Sir Thomas More (c) by Kevin W. Michael | Thomas More, c.1527-1528. Modern portrait, painted in multimedia. A re-painting based on a sketch of Sir Thomas made by Hans Holbein the Younger in 1527 or 1528. The original painting of The Family of Sir Thomas More, made from Holbein's sketches, was lost in the Great Fire of London. It was re-painted in 1593 (by Rowland Lockey) based on the original sketches, which survived. The portrait above is a modern representation based on Holbein's original sketch of Sir Thomas. This interpretation of Thomas More has been painted using vibrant colors for More's robes, in place of the black or dark colors in which we usually see him clothed. In this portrait, he wears a bright violet robe with red and orange sleeves; he also wears the 'S' necklace of Chancellorship. | |||

| Thomas More's Statue at Chelsea, London. Created in honor of the martyr. Patron saint of government, of good politicians, and of people who die for their beliefs. | ||||

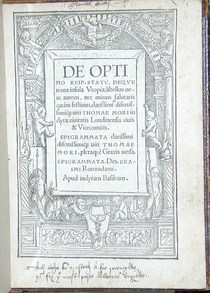

| Early edition of UTOPIA ("No Place" from Greek ou+topos), Thomas More. Design Hans Hobein. Annotations: early owner. | The Household of Sir Thomas More Boston College - St. Thomas More Collection - Fall 2007 |

| Clip from "A Man for All Seasons", 1966 adaptation of the play by Robert Bolt. More is portrayed here by Paul Scofield, in an Oscar-winning performance. <embed height="228" src="http://widget.wetpaintserv.us/wiki/thetudorswiki/page/Sir+Thomas+More+-+Historical+Profile/widget/youtubevideo/1490206501" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" width="276" wmode="transparent"/> | Margaret Roper was Sir Thomas More's favorite child. Like her father, she was a brilliant humanist and scholar. In later years, her own daughters would inherit her intelligence; so would the other women in the More family. The lineage of her direct descendants, like that of her brother John More, has been lost -- possibly forever. |

| <a class="external" href="http://www.tudorplace.com.ar/images/Rich,Richard%281BLeez%2901.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">  </a> </a> Richard Rich, who became a bitter enemy of More's. He delivered what is generally considered perjured testimony to ensure More's conviction. Richard Rich became Chancellor under King Edward VI, and died in his bed. | <a class="external" href="http://blog.siena.org/uploaded_images/Margaret-More-790367.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">  </a> </a> |

| <a class="external" href="http://blog.siena.org/uploaded_images/cecilymoreheron4-739374.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">  </a> </a> Cecily More Heron Sir Thomas More's youngest daughter also suffered for her faith. Like her older sisters, Cecily More was a well-read and educated child, extraordinarily literate for a woman of her times. Her knowledge rivaled that of her sisters. Her husband Giles Heron was convicted of 'speaking too freely'--he was overheard saying something that was considered an insult to the King, even though its 'treasonableness' was questionable. Even so, Giles Heron was convicted of treason and hung, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn on August 4, 1540. | <a class="external" href="http://blog.siena.org/uploaded_images/John-More-737880.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">  </a> </a> John More II Sir Thomas More's only son suffered similar persecution for his own reluctance to accept the Oath of Supremacy. He was never considered as smart and clever as his sisters. Nevertheless, he ultimately followed the example of his father by refusing to compromise himself for something he did not believe in. He was imprisoned and later released. After his release he went to Yorkshire to live with his wife. After his death, his children and later descendants continued to hold independent and controversial beliefs. The children of his sister Margaret More Roper, especially her daughter Mary, were also somewhat controversial. However, Mary Roper chose her words carefully; she produced translations to and from Greek and Latin, as her mother had. Unlike Mary, her cousins--the children of John More--were always mired in controversy. Several of them ended up dying for their faith, just as their grandfather Sir Thomas More had. As with the line of descent from Margaret Roper, John More's line of descent became untraceable after 1758. Regrettably, there is (so far) no trace of others who could be descended from this great and famous line. |

Depiction of the More family by Rowland Lockey, based on sketches done by the original artist, Hans Holbein. The original painting is believed to have been lost in the Great Fire of London that took place in 1666; that original was painted in approximately 1527 or 1528. It portrays most members of the More dynasty, except for Alice Middleton the Younger and some sons-in-law. Note to Contribution: The above painting is called <a class="external" href="http://www.thomasmorestudies.org/g26.html" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">The family of </a>Sir Thomas More c. 1530, by Hans Holbein the Younger. Copy by Rowland Lockey, 1593. | |

For more on Sir Thomas More, click the links below:

Sir Thomas More profile